The following story was published in a special feature section “Mountain Living” in the Hendersonville Times-News on Feb. 26, 1995.

By Jennie Jones Giles

The mythology of nearly all early peoples contains some account of accidental or supernatural happenings which first revealed fire to human beings.

Early peoples regarded fire as a true gift of the gods. It was considered sacred because it was so essential to the welfare of the people.

Because fire was so hard to produce, the custom began of keeping a public fire, which was never allowed to die out.

With the magic of fire mankind could keep predators away and sit in comfort and security. He could cook his food and have warmth and light.

Around the circle of fire grew fellowship and communion. Families gathered around the hearth for security, warmth, food, light and a sense of togetherness.

Therefore, it is not strange that the preservation of fire was an essential part of the life of people who first moved into Western North Carolina.

Matches – the safe, dependable and economical kind – were not commonly available until World War I. The flint and steel method of fire making could be time-consuming and difficult.

Newly married couples always took some fire with them when starting a new home.

If a fire went out, people had to “borrow” fire from a neighbor.

My father, Jack C. Jones, told a story that he was told from his father, Hix Jones, about borrowing fire.

“In 1892, when Daddy was about 10 years old, he spent the night with his sister, Julie, and her husband, Frank Justus. They had only been married a short time. Julie and Frank were the parents of Ernest Justus, the former principal of East Henderson High School and the former Flat Rock High School.

“Being newlyweds they neglected the fire that night and the next morning it was out. The weather was bitter cold with about five inches of snow on the ground.

“They lived about three-fourths of a mile below Frank’s parents (William Davenport Justus and Nancy Pittillo Justus) in a small cabin not far from today’s Peter Guice Bridge which crosses Green River.

“Frank and Julie sent Daddy up to Mr. Justus’ to get some fire so they could have some heat and cook breakfast. He went on up there and brought some hot coals from their house back down to the house on a piece of bark.

“He said he figured they knew how to start a fire with a piece of flint and steel and some charred rag or black gunpowder, but they thought it would be faster to just have him go after some.

‘The oldest fire in the world’

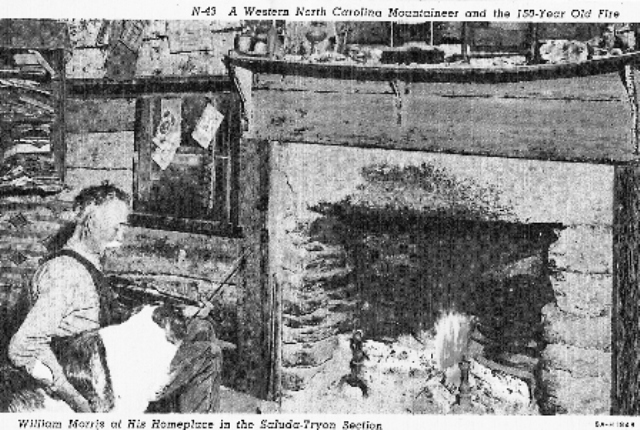

For 164 years four generations of the Morris family kept a fire going in the Holbert Cove area near Saluda that has been called “the oldest fire in the world.”

Billy Morris, who died in 1944 at the age of 84, spent his life keeping the fire going.

The original “chunk of wood” was laid in 1780, Morris told writers in the 1930s and ’40s.

The Morris’ fire became so famous that Billy was asked to appear on a national radio show out of New York City and his story was written in newspapers across the country.

Ed Leland of Saluda took Morris to New York City in 1937 for the radio show.

“He talked a few minutes and played a fiddle on the radio,” Leland said.

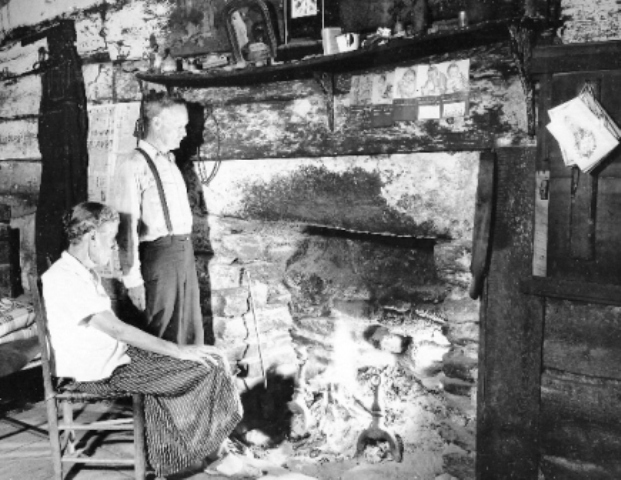

On that show Morris said, “I live alone in a little log cabin back in the hills of Saluda, N.C. I’ve got a little piece of ground, a cow, four pigs and a horse.

“The fire has to be handled with real skill and care. I cover it with ashes and during the day there’s a softly glowing brand resting on a bed of red hot ashes, and it doesn’t give off a bit of smoke.

“After the chores are done at night, I come and stir up the fire ’til it’s a blazing, and then I sit down before it … and I can see in the flames my mother and father, my grandparents and my great-grandparents who started it burning. Sometimes I sit with my old fiddle and play to it.”

Then Morris played “Bonaparte’s Retreat” to a national listening audience.

Lola Ward of Saluda was part of that listening audience. She remembered the radio program that day.

“It was on a Sunday and the family and neighbors all gathered around to hear the show,” she said. “He (Morris) had a great big, beautiful dog that grieved itself to death for him while he was in New York.”

“Simp” Thompson of Saluda also remembers Morris and his dog “Booker T.” Thompson lived farther out Holbert Cove Road than Morris and passed his house on the way to and from town.

“He was a peculiar, old bachelor who wore overalls all the time and played a good ol’-time fiddle. The dog would bark while he played the fiddle.

“Me and my Daddy would go by his house on the way to town. He would throw his foot on the wagon and talk for 30 minutes. Coming back, it was the same way.

“He was a good fiddler. I would stop just to hear him play the fiddle. It would tickle him to death and he would start laughing.

“My Daddy told me they would use flint, the white kind, and take a knife, hit the rock with the knife and hold cotton underneath and catch the cotton afire. They covered up the fire at night. The hot coals kept going.

“Uncle Billy, he loaned people fire when their’s burnt out. People drove miles just to see the century-old fire. It tickled him to death to see ’em and he would talk to ’em.

“He was just an old mountaineer. He loved that old fire and always kept his fiddle tuned. He was extra good.

“The dog slept at the foot of his bed. The dog followed him everywhere.”

George Jones with the Henderson County Genealogical Society also remembered Morris, his fire and his dog. Morris was well-known for telling stories to the young people in the area when they would stop by to hear him play his fiddle.

“I remember one story he told me. He went to town after dark. When he went to start back he heard a rattling-chain noise behind him.

“He started walking faster and faster and started running. Still he could hear the rattling-chain noise and it kept up with him. He got to Friendship Baptist Church and was so scared he ran in and closed the door. The noise kept being around him.

“About midnight he made a run for it and ran all the way to his house, falling on the porch, too exhausted to get up and open the door.

“His dog then came up to him. He had chained the dog before he left home. The dog had broken loose and followed him to town.

“The noise had scared him to death. He thought the devil with a chain was trying to catch him.”

Margaret Thompson Causby still lived on Holbert Cove Road. Her family was Morris’ closest neighbors.

“He would bank that fire at night or if he went somewhere. We loved to hear him play his fiddle. Daddy took care of his dog while he was in New York City. It did die while he was gone. That dog went everywhere he went.

“On Saturdays and Sundays the road would be full of people to see the fire. He kept a flat little box with a slit in the top of it. People would give him money and bring him things.”

Morris died in 1944 and was buried in the Friendship Baptist Church Cemetery.

A cousin, Ida Owens and her husband, Hampton, took over the fire for a while. Local residents say it was only a short time after his death before the fire was allowed to go out.

The hearth fire and the campfire – their magic can stir memories even today. The magic of a fire can still give security and warmth, just as it did to our ancestors.