The early settlers into today’s Henderson County were primarily of English and Scots heritage. There were some folks of Welsh, German, Dutch and French heritage. And several brought slaves with them of African heritage. Scots-Irish is a term often used to describe some of the people of Scots heritage.

Through the years it has often been stated that the Appalachian Mountain people, including the people in Henderson County, were primarily of Scots-Irish descent.

That statement has proven to be incorrect, particularly as related to Henderson County. It is possibly not true for other counties in the Appalachian region.

Documented studies prove that the majority of the Appalachian Mountain people here were about evenly mixed between English, Scots and Scots-Irish.

On this web site is a list from early censuses of surnames of people who lived in what later became Henderson County. Next to each surname is the origin of the surname. Sometimes the surname was common in more than one region of Europe. Extensive documented genealogical studies of many of these families were conducted.

Click on this link for surnames and origins of settlers living in today’s Henderson County on censuses from 1790 to 1810.

Surname Origins – Censuses 1790 to 1810

The term Scots-Irish does NOT mean a person is of Irish heritage. It does NOT mean that the person has a mixture of Irish and Scots.

If a person is of Scots-Irish heritage it means that they are of Scots heritage and their Scots family lived in Ireland before coming to the American colonies. The family could have lived in Ireland for a few generations or only a short while. Sometimes people will actually call their heritage Scots-Irish when their Scots ancestors only left for the American colonies from an Irish port.

Normally, the term Scots-Irish refers to Scots who are Protestant descendants of Ulster Scots, meaning the family came from the Ulster region of Ireland (Northern Ireland).

The English defeated the Irish in 1603, after nine years of war. Northern Ireland was devastated by years of fighting. In order to assure the subjugation of the native Irish people, the king of England granted much of the land to English and Scottish families. In other words, the English and Scots settled on the land of the defeated Irish people.

Fighting continued between the Irish, the vast majority of whom were and are Catholic, and the Protestant Scots and English. A major uprising occurred in 1641 and another in 1688. Violence has continued into the 20th century.

The English and Scots heritage of the Appalachian Mountain people is most apparent in their oral stories, folk tales and myths (Jack Tales are some of the most famous); through music, such as songs and dances; and through their dialect.

It is recommended that everyone watch the movie the “Songcatcher,” a 2000 movie directed by Maggie Greenwald. It is about a musicologist researching and collecting Appalachian folk music in the mountains of Western North Carolina. It’s available for check-out at the Henderson County Public Library and for purchase on the Web and at other locations.

Appalachian Mountain folk dance and songs are of Old English origin, with some Welsh and Scots. Clogging originated in Wales and England, and the step dance is of English origin.

Dialect

The Appalachian Mountain dialect is primarily a mix of Old English, Scots and Welsh. And some German was thrown into the mix.

To hear some examples or learn more, visit:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=03iwAY4KlIUhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=03iwAY4KlIU

http://ncsu.edu/linguistics/ncllp/index.php

Culture

The culture of the Southern Appalachian Mountain people is distinct from most sections of the nation. It is found in Western North Carolina, East Tennessee, southwest Virginia, southeast Kentucky, northwest South Carolina and northwest Georgia.

Culturally, the people have more in common with people in the Ozarks of Arkansas, Missouri, and northeast Oklahoma than they do with people from the Deep South.

But, many of the early settlers came from eastern North Carolina, eastern Virginia and the coastal areas of South Carolina. The Southern geographic location, and experiences during and following the Civil War, left a strong Southern cultural influence also.

Words often used to describe the Appalachian Mountain people are: proud, self-sufficient, independent, deeply spiritual, and private. They have strong family ties; care deeply about traditions, nature and the land; and enjoy farming, hunting and fishing. They are great storytellers with a wonderful sense of often sarcastic humor. They sometimes tend to distrust strangers.

They were frontiersmen who chose to live in the mountains. They chose their lifestyle. They chose farming. They tend to dislike towns and populated areas. They chose isolation. They chose privacy. They were self-sustaining mountain people and proud of it. When the soil “gave out,” or there wasn’t enough land to farm, or families grew too large and there wasn’t land to “pass down,” or there were too many “strangers” moving into the region, many left – mainly from 1870 to 1910. Where did they go? They went to even more isolated areas, away from population centers – Ozarks of Arkansas and Missouri, Idaho, Montana, Washington, Oregon, Texas, and even the mountains of Canada. They almost always settled in mountainous areas or hill country.

Water

When the first settlers entered the area they immediately had to prepare for survival.

The first necessity is water. The people did not dig wells. The ground was too rocky and modern drilling equipment was not available. The digging of wells did not begin until about the 20th century. There are a few instances of early hand-dug wells, but not many.

They gathered water from springs, creeks and rivers. They also used water wheels and pulleys (Lazy Gals). They used the energy of flowing water, “gravity water,” where the water was piped to the porch and ran all the time; and later used water rams that would cut off the continuous flow of the water. Later they would dig a pond on a hillside, locate a pump below the pond, run a pipe from the pond to the pump and have high-pressure water.

The Homestead

The next necessity was to build some type of shelter. The people did not build their homes in the bottom land and they did not build on mountain tops. They typically built in coves and hollows near a water source (spring or stream) and where it was warm and sheltered from cold and wind.

The early houses were log cabins. Log cabins were built and used as recently as the early 1900s. They were not slave cabins, as some people who have bought them and moved them to other locations have been heard to state.

Some people prior to the Civil War began building rough-hewn lumber houses called weather-board houses. Most people began building these after the Civil War.

Prior to the Civil War, there were some farm-type larger houses built, particularly in the Mills River area.

Native trees mentioned by the Cherokee and also used in early pioneer cabin and furniture construction were: Black cherry, Yellow poplar, Shortleaf pine, Sycamore, Red maple, Dogwood, Cedar, Holly, Laurel, Hickory, Walnut, Persimmon and hackberry, White or Chestnut oak.

If they used the bark for shingles or in the making of furniture, they only took the bark from one side of the tree.

Nowhere are log structures more prevalent than in the mountains of Appalachia. Scholars, historians and others are recognizing the need to study and preserve these vanishing architectural remains. The early settlers of the Appalachians built cabins, barns, spring-houses, and other structures of the materials at hand – logs and stone. Trees were felled and hewn into logs, planks and shingles to construct cabins, sheds and barns.

An axe and auger were the main tools. Most of the early log cabins did not have nails or iron hinges. They were too expensive.

The first step in construction was to build a stone or rock foundation, to keep the logs off the ground and prevent rot and insect infestation, and to help level the cabin. The foundations were built from fieldstones and river rocks. The stones or rocks were laid dry, or with mud, one on top of the other.

Once the foundation was laid, settlers would cut down trees and square off the logs. Logs used in house construction were usually of chestnut, oak and poplar. A good working log was generally 12 to 15 inches in diameter and 25 to 30 feet in length. These were hewn flat on either two or four sides, or left round. Early cabins were usually built with unhewn logs. Hewn logs were used later for permanent cabins.

These logs were then “notched” in the top and bottom of each end, and then stacked to form walls. The notched logs were fitted snugly together at the corners of the cabin, and this “interlocking” held the walls in place.

The notching of cabins is studied by scholars to determine the age and origins of log cabins. Saddle or round notching with projecting corners and round logs was one of the most common forms of notching in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. V-notching was characteristic of cabins built by folks of German descent. Full dovetail notching is rarely found in the Southern Appalachian Mountains.

After the logs were stacked, gaps remained in the walls, and settlers had to “chink” their cabins. “Chinking” consisted of jamming sticks and wood chips into the gaps, and then filling in the remaining space with a homemade cement of earth, sand and water. The chinking was then “dobbed” (“daubed”) with mud.

The “crib” was the basic cabin construction. This was a single rectangular room, usually with a loft overhead. A crib was from 10 x 12 feet to 18 x 24 feet in size.

Glass was expensive and rare, so windows were few and typically small. Sometimes mica was used in place of glass. Locally, there was a mica mine on Mine Mountain in the Mountain Page community. Leather straps served as hinges for doors and windows.

Fireplaces and chimneys were built of fieldstone or river rocks. The stones and/or rocks were held together with red clay, which bakes hard from the heat of the fires. Lime was often used to make the clay “set up” harder. Locally, limestone was found in a quarry near today’s Fletcher.

Mantles were usually made of hewn timbers.

The cabins were roofed with hand-split shingles. White oak shingles were the most common in Henderson County.

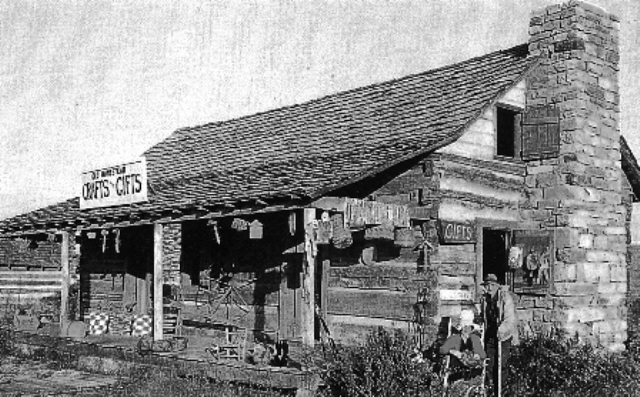

This is a photo of the Hiram King Jones (my ancestor) cabin built probably in the 1840s or 1850s. The cabin was located in the Big Hungry section of the Upward community in Henderson County. His daughter, Emily, and her husband, Daniel Morrison, and descendants lived in the cabin into the 20th century. It was later moved to U.S. 176 and used by the Upward Community Club to sell Appalachian Mountain crafts and plants. This photo is from that time period.

Hiram W. King built a cabin some time in the 1890s in Pisgah National Forest. This cabin is preserved by the Cradle of Forestry.

Floors were generally of wooden planks. Dirt floors were rare in the Appalachian Mountains because the house was built on a foundation.

A “Dog-Trot” house consists of two single-crib cabins joined by a common roof, with a covered breezeway, or “dog trot” between them. Dog trot homes are rarely seen in Western North Carolina, and are most common in east Tennessee. There is an example of a dog trot house at Cataloochee in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Mountain homes frequently had framed rooms added later to the original log portion of the house. These additions served as kitchens and were almost always made after the introduction of sash-saw milled lumber into the mountains. There were at least three lumber mills in Henderson County from approximately 1810 to 1820, and five from about 1820 to 1860.

The placement of frame additions varied, some times in the rear, on one end, or set off in front in an “L” shape.

Two-story log homes typically had two rooms (cribs), separated by a central hall with a stairway leading to a large room upstairs.

Rough-cut hewn lumber replaced logs over many years, some appearing as early as the 1830s and 1840s. Log cabins were still being built in Henderson County after the Civil War.

Covering the interior walls with planks and plaster, boards pasted with newspaper and fabric such as muslin helped with insulation.

Furniture was often crude and simple, usually made with the simple tools at hand.

Log barns and outbuildings were usually built with the spaces between the logs left unchinked.

The mountain farmstead consisted of several outbuildings in addition to the house and barn. Corn cribs, smokehouses, meat houses, tool sheds, springhouses and root cellars all served specific functions in the self-sufficient lifestyle of an Appalachian farmer.

For heat the Appalachian people used open-hearth fireplaces as recently as the early 1900s. They did not have matches. It was important to keep the fire burning. If the fire went out, they would borrow “fire” from a family member or neighbor.

The story of the 100-year-old Morris fire, with photos, is on this web site, “The Keeping of the Fire.” Click on the following link.

They cleared the growth from around the farmstead and women would sweep the yard. They did not grow grass. There were no lawn mowers. They needed to keep snakes, insects and other “critters” away from the house and farmstead.

They loved flowers and blooming shrubbery. Women in the Appalachians were and still are famous for their flower gardens and flower arranging. They also planted flowers, especially periwinkle, on the graves of loved ones.

Clothing, Bedding

Another necessity was clothing. The women weaved, sewed and quilted all the family’s clothing and bedding.

They also used furs (bear, coon) and leather (deer). Cattle were not used for leather, unless the milk cow died.

Some clothing was made from flax, but not cotton. Cotton does not grow in the Appalachian Mountains and it was too expensive for most people to buy. Prior to the late 1800s much of the clothing was made from wool. The people raised lots of sheep for the wool and weaved the wool on hand-looms.

They would save left-over pieces of wool and cloth and worn-out clothing to make quilts. Appalachian quilting patterns are distinctive from the rest of the nation. Most of these quilts are held by families. None are on display in Henderson County. Examples are located at the Mountain Heritage Center at Western Carolina University and the N.C. Museum of Handicrafts in Waynesville.

http://www.blueridgeheritage.com/attractions-destinations/museum-of-north-carolina-handicrafts

To view some Appalachian Mountain quilts located at the Mountain Heritage Center, visit:

http://www.quiltindex.org/contributor.php?kid=1F-BB-0

The women always kept and collected buttons. Everyone had a button collection. Buttons were expensive.

Beef leather for shoes was expensive. Shoes were worn until nothing was left. Deer leather could also be used for shoes.

Women washed the clothes outside over an open fire as recently as the early 20th century, using home-made lye soap. The old black irons, heated over a fire or woodstove, were used for ironing.